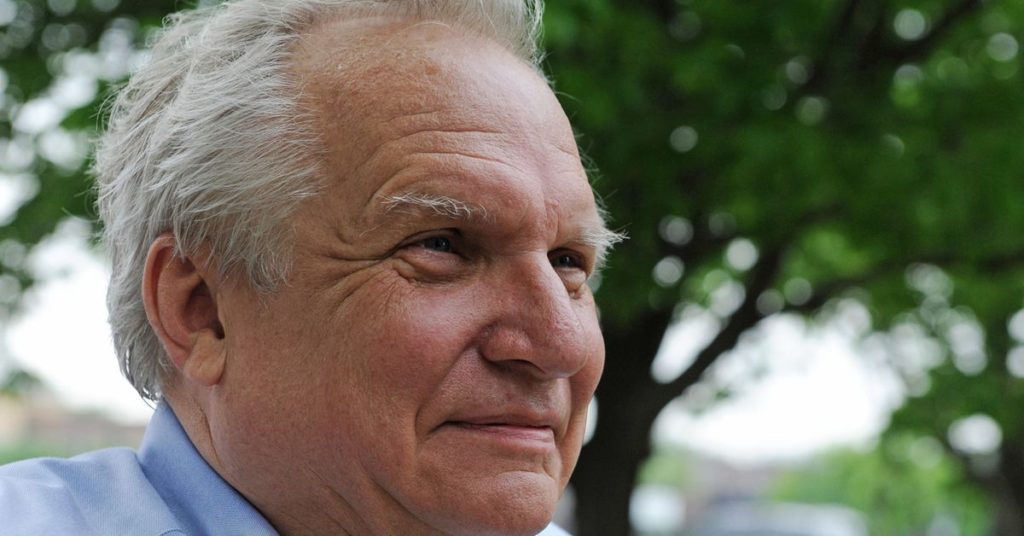

Tim Samuelson is a self-proclaimed “history nerd” who turned a lonely and unpopular existence as a kid into a life-long career that continues to benefit Chicago.

Samuelson recently “retired” from the job he loves as Chicago’s first and only “cultural historian.” But he still has an office at the Cultural Center. He’s still cataloging artifacts he painstakingly collected. He’s just doing it for free. It was, as he put it, “too good of a gig to give up.”

“I can honestly say that, for all of the nearly 20 years I had the job, I never thought about how much money I was making. Money was never the motive for doing. It’s kind of like what I’ve done all my life, as kind of the history nerd that started as a little kid, and here I am almost pushing 70 years old,” Samuelson said.

The love of history in general and Chicago architecture in particular is not a normal attraction for most kids.

Samuelson didn’t learn it from his parents. He hid it from them.

He discovered one of his “first loves” — the work of famed Chicago architect Louis Sullivan — by reading his grandmother’s copy of the Reader’s Digest, which included an illustration of the Carson Pirie Scott building, the Sullivan-designed masterpiece in the Loop that now is home to a Target store.

When his grandma told him that Carson Pirie Scott was where she bought her stockings, young Tim tagged along on her next shopping trip.

Two years later, the Sullivan-designed Garrick Theater was targeted for demolition. A heartbroken Samuelson created what he called a “kid subterfuge.”

He convinced his mom to take him to see a feature-length Mister Magoo cartoon that was playing at the Garrick, then wandered the halls on trips to the washroom.

(The Garrick, near Randolph and Dearborn streets in the Loop, was demolished in 1961 and replaced with a parking garage.)

Pretty soon, Samuelson was making forbidden solo trips downtown on the CTA to look at a list of historic Chicago buildings and stop at the library.

“I was not allowed to cross the busy streets, meaning Touhy, Howard, Western and Ridge. My parents had no idea I was going downtown. There was something about it where I thought, I’d better keep it [on the down] low,” Samuelson said.

Every time he visited a historic skyscraper, Samuelson took a basket along would ask the building carpenter and for a sample doorknob. When he got one, he’d put it in a basket he’d brought with.

“I would go from building-to-building until the basket got too heavy for me to carry anymore,” he said.

“How do you explain the appearance of these exotic doorknobs in the house without blowing my secret gig of going downtown? So I would hide them.”

The “history nerd” who convinced his elementary school principal not to tear the ornamental sheet metal cornice off the top of the building would go on to spend 15 years as a historian and restoration advisor for the Commission on Chicago Landmarks.

There, he helped save many buildings that would have been lost if not granted landmark status. They included the old Chess Records headquarters and several spots in Bronzeville vital to Black history and jazz.

“The stories of Bronzeville were always focused on music. And it’s an amazing history. Those buildings need to be protected,” said Samuelson, who collected jazz and ragtime records as a kid.

“I got all kinds of flack because the landmark commission had never undertaken an abandoned building before. … Every one of them actually was restored, except for one. In fact, there’s even cases where I went personally and boarded some of ’em up.”

It was visionary Cultural Affairs Commissioner Lois Weisberg — who brought Gallery 37 and the “Cows on Parade” exhibit to Chicago — who handed Samuelson the job of Chicago “curator.”

Samuelson remains eternally grateful. “I swoon just thinking about” Weisberg and how “brilliant” and creative she was. Even so, he had one request at the time. He convinced Weisberg to change the title from “curator of Chicago” to “cultural historian.”

“I said, ‘There’s a lot of things that happened in this city historically and still go on today and I don’t want to be considered a curator that’s in any way responsible or fronting for it. I just want to tell the story as it is,’” Samuelson said.

Referring to a history of racial segregation that continues to this day, Samuelson said: “I do hope, through history and example and getting those out there in a really understandable way that it can be its own contribution to chipping away at these terrible situations, mindsets and bad directions of culture and improve things.”