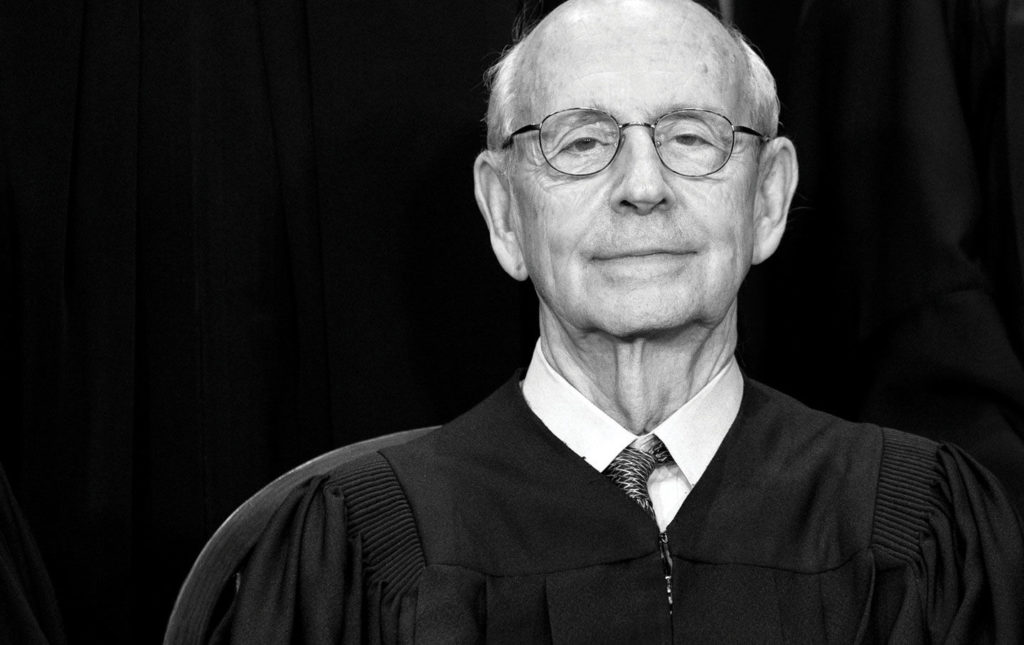

In 1993, Stephen Breyer, then the chief justice for the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston, was hit by a car while riding his bike. He suffered a few broken ribs and a punctured lung. Despite the accident, Breyer left his hospital bed just a few days later and traveled to the White House to interview with President Bill Clinton about an opening on the US Supreme Court.

The interview didn’t go as Breyer might have hoped. Clinton ended up choosing Ruth Bader Ginsburg to fill the vacancy left by Byron White’s retirement. But a year later, another Supreme Court justice retired: Harry Blackmun.

Blackmun, of course, was the conservative Nixon appointee who famously became a liberal stalwart on the bench. It was Blackmun who wrote the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, which, I’m sure, is not something Nixon had in mind when he appointed him. Blackmun’s shift to the left (or, some would say, the court’s shift to the right) was so decisive that he refused to retire during the long winter of the Reagan and George H.W. Bush presidencies. When he finally did, at age 85, Blackmun observed: “It hasn’t been much fun on most occasions, but it’s a fantastic experience,” which sounds like what a gravedigger would say on the day his pension vests.

Blackmun’s pragmatism, and his determination to wait until a Democratic president could nominate his replacement, created a second opportunity for Clinton to appoint a justice—and a second opportunity for Breyer. At 55, the former law professor was touted as a moderate consensus builder who would ensure an easy confirmation at a time when Clinton was worried about the midterm elections and his own reelection campaign. He was confirmed 87-9 by the Senate.

Twenty-seven years later, Breyer finds himself in much the same position as his predecessor was at the start of Clinton’s first term. Like Blackmun, Breyer is still in good physical and mental health. He has served this past quarter century with dignity and decency. He has written around 200 majority opinions and has been a solidly liberal voice on the court, albeit a moderate and pragmatic one. No doubt, there is more he wants to do. But Breyer is 82. He is mortal. And like Blackmun before him, it is time for him to seize the opportune moment and retire.

There is no sense in being delicate about the issue: We’re all going to die, but Breyer is going to die sooner rather than later. And the risk that he’ll do so under a Republican administration is simply not one most progressives paying attention want to take.

The urgency of the situation has inspired a rare outpouring of public calls for Breyer to step down as soon as the current Supreme Court term ends in June. Demand Justice, a group focused on reforming the courts, launched a “Breyer Retire” campaign this spring, complete with a petition and a billboard truck that circled the Supreme Court. (Full disclosure: I was recently asked to join its board.) Paul Campos, a constitutional law scholar, made a desperate case for such an outcome in a New York Times op-ed headlined “Justice Breyer Should Retire Right Now.” And in April, New York Representative Mondaire Jones became the rare elected official to publicly call for Breyer to do so. “There’s no question that Justice Breyer, for whom I have great respect, should retire at the end of this term,” Jones said. “My goodness, have we not learned our lesson?”

Predictably, a small propriety caucus within the Democrats has pushed back, if tepidly, against these calls. Senator Dianne Feinstein, herself 87, recently told CNN that Breyer’s retirement would be a “great loss” and suggested that “producing for whatever the constituency is” was enough. Others, including President Joe Biden, have emphasized that retirement is a personal decision the justice should make without outside pressure.

That’s all very nice and practical, given that there’s nothing anybody can do to force Breyer to give up his lifetime job. He can stubbornly stay for as long as his body will let him—but the reality is that he shouldn’t. It is a bad, illogical, personally selfish decision to stay, even for just another year. The Democratic majority in the Senate is tenuous. In the event of the death of a single Democratic senator from a state with a Republican governor, that majority evaporates. Mitch McConnell and his fellow Republican senators have proved that they will not confirm any justice appointed by a Democratic president. Every day that Breyer stays is a day the Republicans get another spin on the random wheel of death, looking to get just one more vote to block his successor.

And that’s assuming Breyer wants to play Hamlet for only a year. Waiting until after the next presidential election, or even until after the upcoming midterms, would be straight-up political malpractice.

We have all just witnessed the con-sequences of leaving these decisions to fate. In 2012, after Barack Obama won a second term and Democrats picked up two seats in the Senate, bringing them a three-vote majority, some (myself included) suggested it was time for Ginsburg (may her memory be a blessing) to retire. Ginsburg, by that time, was already an 80-year-old cancer survivor. While the legend of the “Notorious RBG” was growing, Father Time remained, then as now, undefeated.

But Ginsburg refused. The calls for her to retire were muted by accusations of sexism, and those accusations were not entirely off base. Antonin Scalia was an obese 75-year-old in 2012, and I doubt conservatives would have been clamoring to get him off the court had Mitt Romney won that election. At the same time, it seems that Ginsburg really believed Hillary Clinton would succeed Obama in the White House, and the prospect of being replaced by an appointment from the first woman president inspired her to serve through one more election cycle.

That decision didn’t work out well for the country: Clinton did not win, and Ginsburg did not outlive the ensuing Republican administration. She died after the election that would replace Donald Trump had started, and Republicans greedily rushed to fill her seat with Amy Coney Barrett—a woman, yes, but one who is an active threat to all of the issues and constituencies Ginsburg held most dear. By trying to be replaced on her own terms, Ginsburg created an opportunity for Republicans to undo her work.

Ginsburg perhaps thought herself irreplaceable. Breyer might, too. It’s an understandable affliction that befalls people who can change entire industries or protect whole classes of people with a single sentence. But Supreme Court justices are not indispensable—their votes on the court are. Women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community don’t need Stephen Breyer to defend our basic rights; we need five votes to do that work. There are plenty of people who can vote the way Breyer would (some of them are even members of the various vulnerable communities constantly under attack), and most of those candidates can continue to vote that way long after he has slipped this mortal coil.

Unfortunately, Breyer doesn’t appear to see things this way. He appears to think his value (and the value of any justice) is in their individuality, not in the reliability of their opinions. Ironically, the very qualities that made Breyer a safe, consensus pick for the Supreme Court in the first place might now make him obstinate in the face of calls for his retirement. Breyer is no ideologue. He does not believe that party affiliation is the critical factor in court decisions. He’s been quoted saying that “politics goes out the window” once justices ascend to the court and that “where there are differences [in opinions], those differences are drawn less on the basis of…politics.”

Breyer has been an unflagging proponent of comity and collegiality on the court, writing in his 2005 book Active Liberty that he “never heard one member of the Court say anything demeaning about any other member of the Court, not even as a joke.” But when Breyer recently dissented from Barrett’s first majority opinion (a victory in service of authoritarianism that limited the scope of the disclosures required under the Freedom of Information Act), he wrote simply, “I dissent,” shocking court watchers by omitting the customary phrase “with respect” from the sentence. He later edited his dissent to make sure it included that word for posterity. Because, sure, while Barrett is the product of raw partisan politics, someone who was picked specifically to take away reproductive rights—rights that Breyer has spent his career defending—that’s no reason to hurt her feelings.

These views on comity and the fundamentally apolitical nature of his calling might explain why Breyer is staffing up. Reports indicate that he’s already hired his law clerks for the 2021-22 term. That’s a strong indication that he plans to stay on for at least another year and punt the conversation about his retirement to the brink of the 2022 midterm elections.

Partisan pressure might make Breyer dig in his heels. In March, Noah Feldman observed in Bloomberg News: “The more the timing of his retirement is depicted as a partisan objective, the less he will want to do it. To be seen to retire ‘in order’ to let Biden pick his successor would betray Breyer’s own career-long objective of making decisions based on what is right for the country, not for one party.” Where I see a court that is 6-3 in favor of conservatives, Breyer likely sees nine individuals trying to noodle things out the best they can.

With Ginsburg’s passing, Breyer is the most senior liberal on the court, meaning that when it’s time to write the dissents that he, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan will surely be writing, he will often get to choose who writes them. It’s a power he hasn’t had before, and one that could be used to build consensus, if that were a thing. I imagine Breyer will enjoy that role, given his belief that conservatives on the court can be reasoned with.

Breyer’s views on the apolitical nature of the court, and his new power to shape it, would be interesting if they weren’t so provably false. In reality, the court is divided by partisan politics, whether the justices wear their MAGA gear underneath their robes or not. Writing about Breyer’s belief in the possibility of consensus building in The Yale Law Journal, professor Paul Gewirtz called this notion “illusory.” And that was in 2006.

Trump promised to appoint only justices who were against women’s rights, and senators like Josh Hawley promised to confirm only such justices. Does anybody sincerely believe that Trump’s appointees to the court (Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, and alleged attempted rapist Brett Kavanaugh) agree that “politics goes out the window” when that issue comes up? Is there any doubt that those three are more politically strident about the issue than the justices they did replace: Ginsburg, Anthony Kennedy, and, in the case of Gorsuch, Merrick Garland, whose rightful seat he occupies instead? Breyer can live in a world of wishes, rainbows, and unicorns where consensus building is a thing, but I submit that those of us who have some of our human rights on the line do not have the luxury of watching Breyer tilt at windmills while he plays chicken with death.

I submit respectfully, of course.

Breyer is a good guy, and it is fundamentally sad that he needs to retire simply because the stakes of losing his seat to the Republicans are too high. It’s sad that we have to call on justices to retire based on some actuarial table of life expectancy and the number of votes available in the Senate. The only American who will be asked more about his retirement in 2021 than Stephen Breyer is Tom Brady.

The truth is that lifetime appointments are an absurd way to staff a federal judiciary in a country that shrugged off monarchy two and a half centuries ago. But there are alternatives. The solution to the reality of Breyer’s advancing age is to end lifetime appointments and institute term limits. The solution to the problem of indispensable justices is to expand the number of seats on the Supreme Court and thus make each individual justice less important. Indeed, progressives should be focusing their energy on achieving these long-standing judicial reforms, instead of having to flash the lights on and off until Breyer figures out it’s time to go home. We can do better than this. We can be a country that doesn’t have to beg octogenarians to quit.

Breyer is against court expansion, but he is open to the idea of term limits. He has said, “I think it would be fine to have long terms, say 18 years or something like that, for a Supreme Court justice. It would make life easier. You know, I wouldn’t have to worry about when I’m going to retire or not.”

I won’t presume to tell Breyer how to make his life easier, but I can tell him how to make life easier for the country. He’s had this job for 27 years. He shouldn’t make everyone else worry about a 28th.