More than four years ago, Southwestern College’s accreditation was on warning status, the college was grappling with multiple employee discrimination or misconduct complaints, and the campus was grappling with a history of racial tensions.

Today officials say the college has gotten back on its feet and is out of crisis mode, although it’s still facing some challenges.

In the past few years the college got its accreditation reaffirmed, completed 70 out of 79 personnel misconduct investigations and survived a bout of racism accusations during the 2019 student government election that threatened to tear the campus apart.

“The college is not in the same place where it was then,” said Christian Sanchez, who was the Southwestern College student government president last year. “Of course, there’s still work to be done, but I think there’s been a drastic improvement.”

Some of the racial challenges linger.

For instance, five Black current and former employees sued Southwestern last year alleging discrimination, including being passed up for promotion, being denied overtime and hearing racially offensive comments.

The college said it is reviewing the lawsuit and taking the allegations seriously.

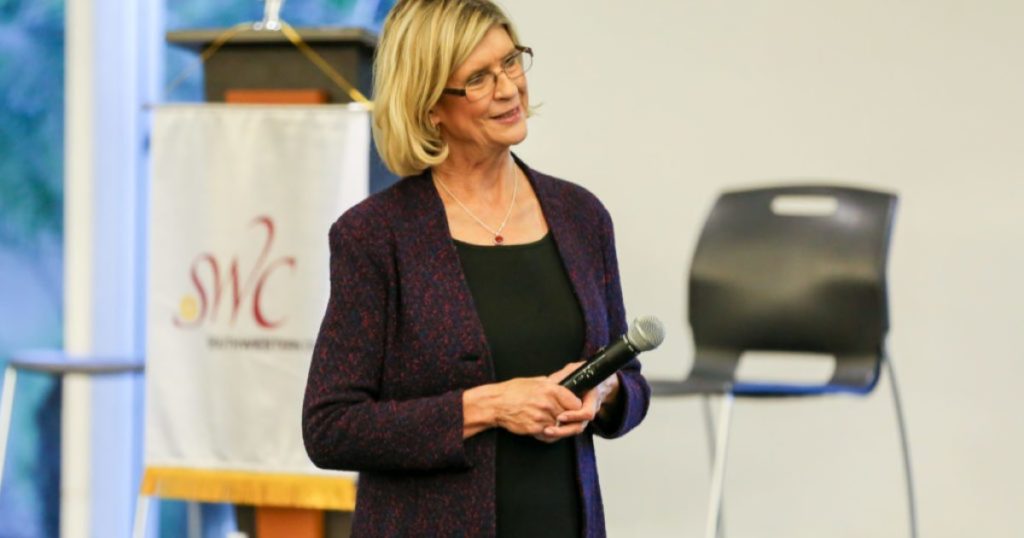

Still, Sanchez and others at the college give credit to Kindred Murillo for the progress the college has made. Murillo, the college’s superintendent/president, was hired more than four years ago to help save the college.

Now Murillo is wrapping up her work and will retire on March 19.

Her successor is Mark Sanchez, assistant superintendent for student success and support programs at Cuesta College, a Hispanic-serving institution in San Luis Obispo. The Southwestern College board hired him last month on a $250,000 annual contract.

He is not related to Christian Sanchez.

Mark Sanchez, the new superintendent/president of Southwestern College.

(Southwestern College)

Murillo said she hopes the college continues to make progress on its racial challenges.

“The diversity, equity and inclusion work needs to continue,” Murillo said. “The college is not where it needs to be at; there’s still a lot of work that needs to happen.”

Throughout her term, Murillo was frank about Southwestern’s problems with race and equity and vocal about wanting to fix them.

“It didn’t take me long to be on the campus to very clearly see that it was anti-Blackness,” Murillo said in 2019. “As a White person, my job is to do something about it, not to stand by and be passive about it.”

To get the college through crises like the 2019 racially polarized student government election, Murillo and college leadership commissioned internal investigations to find the facts behind several complaints, then they used those facts to hold people accountable and to discipline employees who they said had committed misconduct.

“Really trying to create an inclusive environment has been the major work, and that means that you have to hold people accountable,” Murillo said. “That’s hard work because you’re really saying we have rules, I have policies, and you have to follow those. And that hasn’t always been the case at Southwestern.”

At the same time, Murillo held forums where students and others could voice their concerns and feelings. Those helped, said Christian Sanchez, because they made students feel like they could share their thoughts without being attacked or judged.

“Changing systems that have never been built for everyone … especially marginalized people, is never an easy change and can be painfully slow,” said Leticia Cazares, Southwestern College board president.

“But despite the difficulties, (Murillo) has persisted and doubled down on our goals by really working hard at ensuring that we are all working together, that we’re listening to our students and we’ve been making great headway around the cultural and structural changes that will sustain the work we’re doing moving forward.”

NAACP San Diego said it is important for Southwestern to hire more Black faculty, administrators and other staff to address racism on campus.

NAACP San Diego was involved in a 2017 lawsuit by three custodians who alleged racial discrimination and harassment at Southwestern. The suit was settled in 2019.

“Creating one or two positions will not do,” said Katrina Hamilton, education chair for NAACP San Diego. “Oftentimes African Americans are placed in silos or are the only ones in their departments where they are isolated and attacked by others; such is the case of (Southwestern). Schools must do a better job in supporting and retaining Black educators for not only Black students and families but for all, towards the betterment of humanity.”

Under Murillo’s leadership, college officials instituted a slew of changes aimed at improving racial equity, including efforts to hire more diverse staff.

The college instituted implicit bias training for hiring committees, mandated a minimum level of diversity for hiring committees’ membership, and standardized hiring processes to reduce subjectivity in the screening and selection of job candidates, Murillo said.

By 2019, more than half the college’s employees and almost two-thirds of its administrators were people of color, compared to 43 percent of employees and 54 percent of administrators in 2016.

Within those employee numbers, some minority numbers grew while others didn’t.

The percent of Latino employees at Southwestern grew from 25.9 percent to 33.8 percent, while the percent of Black employees stepped up from 4.7 percent to 5.4 percent. The percent of Asian employees fell from 11.9 percent to 9.6 percent.

In total, about 90 percent of Southwestern students are students of color, including 69 percent Hispanic students, 9 percent Filipino students and 4 percent African-American students.

Murillo’s executive leadership team is 75 percent people of color: out of eight members, two are multiracial, one is Black, two are White, one is Middle Eastern and two are Latino.

So far 40 faculty have completed the college’s new “Advancing Equity Teaching Academy” — which educates about equitable teaching practices — and 40 more are currently enrolled.

Murillo also helped create the college’s Office of Equity and Engagement, which has been working on writing an anti-racism plan for the college.

The college also started offering Jaguar Pathways, a program that streamlines students’ coursework so they can complete their degrees and exit college more quickly.

Southwestern’s eight-year graduation rate was 17 percent in 2017; now it’s 25 percent.

That’s an improvement, but not good enough, said Murillo, who wants the college to get to at least 50 percent.

“This has been the hardest job I’ve ever had. But it’s been the most fulfilling work,” Murillo said.

New leadership

Mark Sanchez said in an interview that he plans to continue the work on equity by Murillo and others.

“I want to ensure that everyone feels valued,” he said. “I want to ensure they feel heard, that they feel like they’re contributing to the institution meeting its mission.”

Sanchez graduated from Southwestern in 1993 before transferring to Point Loma Nazarene University and later receiving a doctorate in educational leadership at California State University, Fresno.

“It was a very personal decision to return home to a college … which had a really strong stake in my personal and educational development,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez has worked more than 20 years in community college administration, the last three at Cuesta.

Under Sanchez’ leadership, Cuesta has opened a Dreamer center to support undocumented students and some student food pantries and provided application, financial aid and counseling services at a local military base. Cuesta also increased mental health counseling hours from 20 to 45 hours a week, including bilingual counselors, Sanchez said.

The pandemic has decimated employment for many, so Sanchez made it one of his goals at Southwestern to partner with local businesses to develop more job programs. For example, officials at Cuesta saw a shortage of teachers at K-12 schools, so the college offers a teacher pathways program, where it partners with universities to get more new teachers credentialed, he said.

“Anything that’s going to help someone transition into a sustainable living career, a sustainable wage-earning career, is really what the mission of the institution should be about,” Sanchez said.