ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — There is no before and after for University of New Mexico professor Eva Encinias.

There’s only always.

Eva Encinias conducts a flamenco class for kids at the Tierra Adentro Charter School in 2014. She has retired from teaching at the University of New Mexico but will stay involved with the charter school. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

That’s how long dance has been a part of her life. Her mother, Clarita Garcia de Aranda Allison, owned a dance studio in the North Valley near Edith and Candelaria.

“I was raised in her dance studio,” she said. “I learned tap, ballroom, and traditional folk dances from different regions in Mexico. But flamenco was her signature and I became immersed.”

……………………………………………………….

Encinias, 67, did more than add her own signature to the traditional Spanish style of dance. She wove it into the cultural fabric of New Mexico.

Encinias, 67, did more than add her own signature to the traditional Spanish style of dance. She wove it into the cultural fabric of New Mexico.

She built the flamenco program at the UNM, started Festival Flamenco de Alburquerque which draws audiences and dancers from around the world to the state.

Flamenco dancer and University of New Mexico professor Eva Encinias performs in this undated photo. (Courtesy of Eva Encinias)

In 1992, she opened the nonprofit National Institute of Flamenco studio that provides after-school music and dance classes among other things. Hundreds of students have cycled through her classes, many going on to have their own successful careers. UNM is still the only place in the world to get a flamenco degree in a university setting.

Encinias announced this winter that she is retiring from UNM after 43 years.

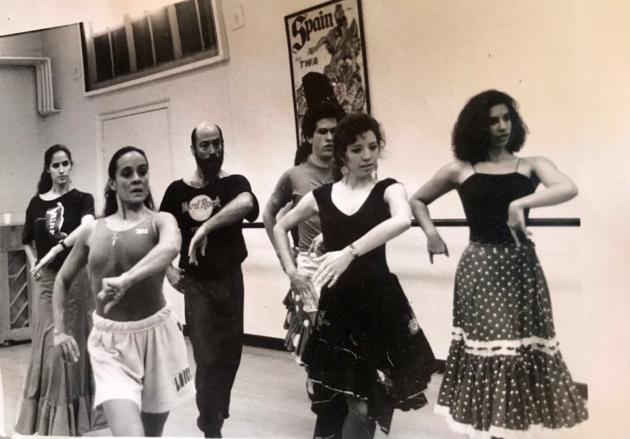

Eva Encinias leads an advanced flamenco class at the University of New Mexico in this old photo. (Courtesy of Eva Encinias)

“I thought it was important for me to retire so the younger blood can get in there,” she said. “But I’m still young enough. I have projects I want to do at my house. I’ll have more time to read.”

She also plans to stay involved with Tierra Adentro of New Mexico – a sixth-to-12th-grade charter school that her son Joaquín Encinias helped found. The school has a focus on dance and music and Joaquín Encinias is the director of curricular implementation.

“Using flamenco and dance is part of our vision in education,” she said. “We believe dance is a vehicle for students to explore things not familiar to them.”

Encinias did not plan on becoming one the state’s premiere flamenco instructors and educators. She simply wanted to dance.

Eva Encinias, middle, poses with her daughter Marisol Encinias and son Joaquín Encinias in 2006. (Adolphe Pierre-Louis/Albuquerque Journal)

“I realized I wanted to continuing dancing after I graduated from high school,” she said. “But there were not a lot of options (to learn flamenco). I knew if I wanted to continue studying flamenco, I would have to leave. I didn’t want to leave because I love New Mexico.”

She had already given birth to Joaquín Encinias and his twin sister Marisol Encinias. She decided to go ahead with a general dance degree at UNM. Instructors knew about her background in flamenco and asked her if she would be willing to teach a course in flamenco. It was enthusiastically embraced by students.

“Then it became two courses,” she said. “Then it became three courses. Then I never left.”

The university asked her to develop a program of studies specializing in flamenco. She worked it at it, building on the curriculum each year. She leaves the school with a robust list of course offerings that allows students the opportunity to minor in the subject.

Joaquín Encinias said his mother is a light-hearted person with a great sense of humor who required he and his sister to take two dance classes a week and play a musical instrument when they were growing up. She allowed them to stop when they were 15 and to decide for themselves if they wanted to continue. Both followed in her footsteps, becoming professional dancers. Marisol Encinias is now the director of the National Institute of Flamenco.

“Her legacy, I hope people know, is she cares deeply about artistic creativity and vision,” Joaquín Encinias said. “She knows it deserves a place in our community.”

John Truitt, the retired Albuquerque Academy director of bands, met Encinias when she was a teenager dancing in her mother’s studio in the late 1960s. Truitt was a young musician just starting out in his career and was wanting to become a flamenco guitar player. His teacher invited him to attend a dance rehearsal at the studio.

“I got this big blast of energy from them, but especially from Eva,” he said. “She was just 16 at the time, but she was amazing and a perfectionist. I thought ‘This is where I really want to be. I love this.’ ”

The two would go on to become colleagues and then lifelong friends. He played for classes at UNM and other events. Her expectations for everyone, he said, are high. She pushes others to be their best.

“I took one of her flamenco classes one time,” he said laughing. “Even as her good friend, she gave me a ‘C.’ ”

He said Encinias is skilled at building support for her ideas. In a class of 50, she will know everyone’s name and something about each of them.

“She has unbounded energy,” he said. “She’s described as a force of nature. She’s simply a person you cannot say ‘No’ to. She describes herself as a bulldog.”

Truitt recalled the time a performer from Spain tried to change the terms of his contract minutes before going on stage. After hearing the roar of the crowd, he demanded double the pay. Truitt said everyone backstage was stunned but Encinias didn’t hesitate.

“She told him ‘No. You are going home. I’ll call a cab right now,’ ” he said. “And she did. Then she went on stage and told the audience verbatim what he had said. Then she told them ‘I am here, my son is here and so is my daughter. We will finish the show.’ The crowd erupted into cheers and screams.”

Although it was recently reported that her family emigrated to the United States after the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, Encinias said her family has been in New Mexico since the 1700s. She said the state’s ties to Spain have made flamenco’s rise in popularity no surprise. She said people see it as a ritual practice. A mode of expression that is completely engaging and powerful. It was a feeling she herself channeled, forever cementing her connection to the world of flamenco.

“She’s mostly stepped away from performing, but she was a beautiful dancer,” Truitt said. “She was spectacular. Jaw dropping. She had speed like nobody I had ever seen.”